I spent the summer of 1979 in Oneonta, New York where I had just finished sophomore year. Barely.

My grades were terrible and had been since freshman year. In fact, they were so terrible that the Hartwick College provost asked me to dis-enroll, a polite way of saying I’d flunked out. So, in the fall, I would be transferring to the University of Maryland, where my 2.75 GPA made the cut. And I would now be responsible for paying the instate tuition with student loans–my father would pay only for room and board. Had he been right all along? Was I not college material? Was I as stupid as my grades might indicate? Why had I chosen to attend a private liberal arts college in the Catskill foothills, far from the comfort of my mostly Jewish upbringing and attendance at a progressive private school in Baltimore?

Had I known about culinary school in those days, I might have gone there instead of pursuing a four-year degree. It probably would have suited me better. My love of food and cooking was nothing new, having grown up with a mother who instilled in me her passion for cooking and entertaining. At about age fourteen, I was sometimes responsible for making dinner on the nights my mother attended graduate classes at the University of Maryland School of Social Work in downtown Baltimore. Those were the nights I first learned the power of feeding people, that I could share bits and pieces of myself without uttering a word.

In that summer of 1979, I shared an apartment with two roommates. I decided to bake a challah as a way of saying goodbye to them, to Oneonta, to leave a part of myself behind. Not many Jewish people went to Hartwick or lived in Oneonta. My roommates knew that challah was a braided bread but had never eaten it. I had already told them that challah was even better the second day as thick-cut French toast dunked in maple syrup. I was about to rock their world, rock being the operative word here.

Had I ever made a challah before? Nope. Not once. Had I ever baked even one loaf of bread? Uh…no. But I was (and am) determined if nothing else. So on one of the hottest, most humid days in August, I attempted to bake a challah. All I can say is that there is truth to the adage practice makes perfect. I killed the yeast by using water that was way too hot. The dough never rose, didn’t even budge. Braiding it was out of the question. I decided to bake it anyway. As I waited for the oven to pre-heat on that ninety-degree day, I said the usual things I say to myself when trying to feel better like: How bad could it be? It’s the thought that counts, right?

Well, remember that rock I mentioned a minute ago? Challah is an egg-based yeast bread. It’s supposed to be light, pillowy, soft, yielding. Mine was…not. It was heavy, dense, impossible to cut. I managed to hack it into slices that mostly resembled biscotti. My roommates slathered the pieces of hard as rock challah with room temperature butter, topped with a drizzle of honey from the plastic honey bear that sat on our counter. They were nice enough to tell me it was the best challah they’d ever had.

Those were some darn good roommates.

A decade passed before I attempted to bake challah again. It bore little resemblance to the Oneonta challah. I even managed to braid it. But like the Oneonta challah, it was made in a place where I felt like an outsider. A place where if I wanted to serve challah on sabbath–and give my young son a taste of Judaism–I was going to have to bake it myself.

So let’s fast forward to 1990 and the incident that turned me into a fearless challah baker.

I was at the grocery store with my young son who was sitting in the basket of the grocery cart. In the middle of the canned goods aisle, a woman, grocery tote hooked over one arm, said to me, “Oh, he’s so cute! How old is he”?

“Thank you. He’s almost a year old. His first birthday is next month.”

“You must be new in town. I don’t think I’ve ever seen you before.”

I had just moved to Carlsbad, New Mexico where my husband’s job required us to live. It is a town of 25,000 in the southeast corner of the state bordering Texas. Think sage brush, dust devils and mostly conservative people, some with twangy accents.

I couldn’t believe this woman in her mid to late sixties was asking me if I was new in town. In the month that I had lived in Carlsbad it was clear the town was stuck in some kind of time warp. There was a definite we still think it’s the 1950’s and we’re proud of it, vibe in the air.

This woman, a total stranger, then asked me, “What church do you go to?”

I paused for a second, debating my answer. Part of me wanted to pull a U-turn right there in front of the canned soup. Instead, I decided there’s nothing like the truth.

'“I’m Jewish. I don’t go to church.”

This was 1990, a mere ten years before we would be entering a new millennium. It was hardly the dark ages. But Carlsbad, New Mexico was still a place where teenagers “cruised” on Friday nights, where people graduated high school (or not) and never left town, and where church going was a major event.

The woman proceeded to take a few steps to one side, then the other. Her eyes darted towards my back, like she was looking for something behind me. I shifted too, wondering what she was doing, what she was trying to see.

“What are you trying to look at back there?”

“Oh, well, I’ve never met a Jewish person before. I’m just lookin’ for your horns.”

Had I just heard her correctly? I was sure I had. And there was no mistaking that she had deliberately looked behind me, checking for HORNS!

“Well, sorry to disappoint. I guess I must have left them at home today.”

At this point, I did make that giant U-turn and got the hell out of the grocery store.

That’s when I decided to start making challah. Andrew isn’t Jewish. But we agreed we would give Austin as much exposure to Judaism as possible. I wasn’t and still am not a very observant Jew, but I enjoy celebrating the holidays, occasionally observing the Friday night Sabbath. It was very clear I was going to have to do this without the benefit of a local Jewish community or my family, two time zones away on the east coast.

The next time I went to the grocery store I bought yeast and a cooking thermometer. Nothing, especially overcooked yeast and ignorant people, would stand in my way of learning how to bake challah. The Carlsbad challah bore little resemblance to the Oneonta challah. I managed to NOT kill the yeast so the bread rose. I braided it. It turned golden, nut brown in the oven. We slathered it with butter. We even had leftovers for thick-cut French Toast the next morning.

In the eleven years between baking my first and second challah, I’d graduated college, worked as a caterer and chef to a college president, moved three times, gotten married, mourned and mourned some more my mother’s death, and given birth to a son. Carlsbad was proving itself to be a place like no other. But baking challah in Carlsbad was my way of kicking its ass.

Challah Recipe: Makes 2 loaves

I take no credit for this recipe. It is adapted from Beth Hensperger’s recipe from her cookbook, The Bread Bible which came out in 1990. Hensperger, a food writer and cooking instructor, died in 2021.

If you’ve never made bread before just remember that yeast is a living microorganism. Yeast needs warm water between 100-110 degrees Fahrenheit and a bit of sugar to become active. You can use a cooking thermometer to make sure your water is at the proper temperature. If you don’t have a cooking thermometer, dribble a few drops of water on the inside of your wrist. It should feel just slightly warmer than your body temperature. If you say OW, it’s too hot!

The flour measurement is a bit imprecise but you want the dough to hold together without being sticky. Aim for it to be soft as a baby’s butt.

I’ve included measurements in grams and milliliters if you prefer to weigh ingredients.

Sometimes, I make the dough the night before I want to bake the loaves. Letting the dough rest overnight in the refrigerator, letting it sit at room temperature for about an hour before I’m ready to shape it. This long, slow rise allows for more flavor development.

If you have a stand mixer with a dough hook attachment for kneading you can absolutely use it. I usually do, but it is also easily made using a sturdy wooden spoon, a metal whisk and a bit of elbow grease.

The dough needs to rise twice, first for 75 minutes and again for 45 minutes, so plan accordingly. And don’t forget to make Challah French Toast with the leftovers! That is, if you have any.

Ingredients:

1/2 cup granulated sugar/ 3 1/2 ounces or 100g

2 envelopes dry active yeast

1 Tablespoon salt

1 3/4 cup water, 100-110 degrees Fahrenheit/ 397.25g OR 425ml

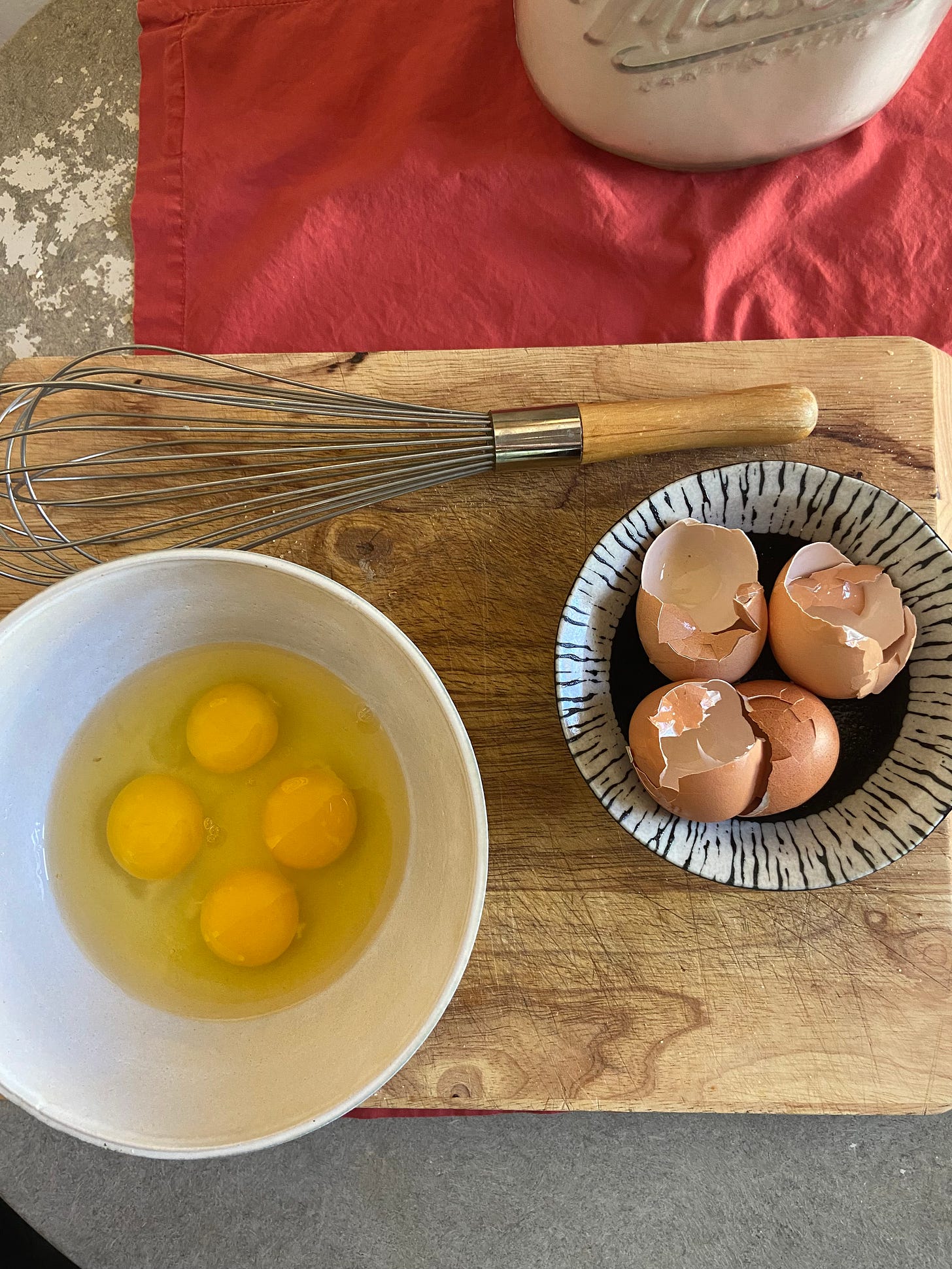

4 room temperature eggs

1/2 cup vegetable oil/ 3 1/2 ounces or 99g

8-9 cups all purpose flour/ 34 ounces or 960-1080g

About 2 Tablespoons vegetable oil to grease bowl dough will rise in, plus a bit more to grease baking sheets

Glaze:

1 room temperature egg mixed with 2 Tablespoons milk

Poppyseeds or sesame seeds for sprinkling on top before baking

Instructions:

Combine sugar, yeast and salt in a large bowl. Whisk in water, eggs and vegetable oil. Add 4 cups of flour and whisk until smooth, about 3 minutes. Now switch to a wooden spoon and add in remaining flour, 1/2 cup at a time until a soft dough forms.

Knead on a floured surface until dough is satiny, about 10 minutes, kneading in more flour if sticky.

Grease a large bowl with 2 vegetable oil. Add dough turning to coat entire surface. Cover bowl with a kitchen towel or plastic wrap. Let rise in a warm, draft-free area until doubled, about 1 1/4 hours or 75 minutes. Dough should be roughly doubled in bulk.

Grease 2 baking sheets. Gently knead dough on a floured surface until deflated. Divide dough in half using a serrated knife or metal bench scraper. You can eyeball this or use a kitchen scale. Divide each half into 3 pieces. Roll each piece into a 15 inch rope. Form 2 braids, pinching and tucking ends underneath. Transfer braids to pans, cover each braid with a kitchen towel and let rise again for 45 minutes.

Pre-heat oven to 375 degrees.

Mix 1 egg with 2 tablespoons milk. Brush mixture over loaves with a pastry brush. Then sprinkle with either poppy seeds or sesame seeds.

Bake loaves for about 30-35 minutes. The internal temperature of the challah should be between 190-200 degrees Fahrenheit. It should be golden brown on top and slightly browned on the underside.

Cool on wire racks before slicing and eating. This is the hardest part!

Wow, what a story! Absolutely loved this. Thank you for sharing. And my horror at the woman in the grocery store!! Unbelievable. Love that you are baking your own challah for your child.

As a once-tentative, now-confident challah baker myself, I loved this story. Welcome to Substack! 🤗🍞